September 2021

Monthly Archive

Monthly Archive

Posted by Jim DeLaHunt on 30 Sep 2021 | Tagged as: Canada, community, Democratic Reform, politics

Canada held a national election 10 days ago. I have watched and voted in US elections for 40 years — first in California, where I spent my early adulthood, and later Washington state. I have been watching elections in Canada for 15 years, since I immigrated in 2005. I first voted here in 2017, after becoming a citizen. But in this election, on 20. September 2021, I served as a poll worker for the first time. This gave me an insider’s view of how this election was run. As an engineer, I love the process and methods in use around me. I can’t resist writing down some of the differences in election mechanics, between this Canadian election, and the California and Washington election mechanics which I have experienced.

One issue. This election was about one issue: electing members to a national Parliament. There were no other races. Nothing from the province or city. By contrast, the US elections I know usually piled multiple races and initiative questions into a single election and a single ballot.

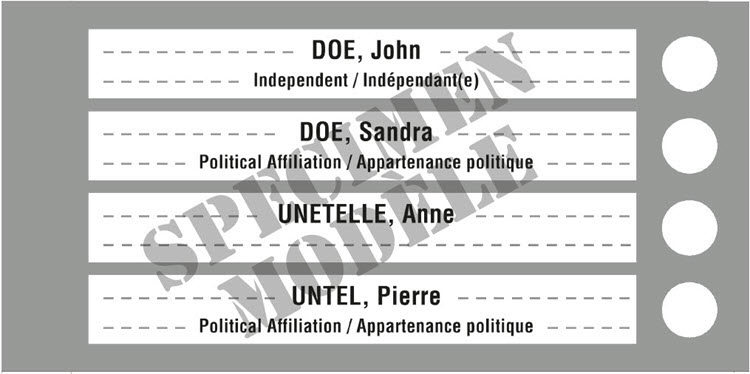

A small, simple ballot. The ballot was a single slip of paper, slightly larger than the palm of my hand. The only issue was the general election to the Parliament. Canada’s current electoral system, the archaic “First-past-the-post” system, meant that voters at my location voted only on candidates for one electoral district. The above sample has four names, but our ballot had five names.

Very manual ballot marking. A voter filled out the ballot with a pencil or pen. They put an “X” or check-mark or solid fill-in in one of the circles. Then the voter folded the ballot back up, and (after tearing off a stub) put the ballot in the ballot box themselves. By contrast, for Washington elections the voter must fill in a space on the ballot in a way that a scanning machine can read. (The same is true for Vancouver municipal elections.) In California, I sometimes filled in scannable marks on a paper ballot, and sometimes tapped in choices on a voting machine’s computer screen.

One elections office. All the voting in this election, nationwide, was operated by a single office, Elections Canada. A separate organisation, Elections B.C., runs provincial elections, and a city department runs Vancouver municipal elections. By contrast, in both California and Washington, election operations are delegated to county-level elections offices. These offices run elections for municipal, county, statewide, and national races. In the US, I currently vote through the services of the Whatcom County Auditor’s Office.

Very specific geographical ballot boxes. Elections Canada divided the electoral districts into small, local “poll divisions”, each with a specific voting desk and ballot box. I was the Deputy Returning Officer for Poll Division 125 of Electoral District 59034 (Vancouver Centre). This corresponded to two condo towers, one on Robson Street and one on Hamilton Street. People at those addresses voted at my desk. If they waited in line, they waited with their neighbours. People at other addresses voted elsewhere. I was located in a room in the Vancouver Public Library’s main branch. Our room had perhaps 10 voting desks and 12 poll divisions. Some desks and ballot boxes embraced two poll divisions. One curious side effect of this is that some voting desks had long lines, and some had none, depending on how many neighbours turned out to vote. There was no taking the next open voting booth of several equivalents, as in California. And of course, Washington has 100% mail-in voting, so it is much different.

Very voter-friendly rules. As right-wing politicians in various US states try to set up voting rules to exclude participation by citizens they don’t want, it was refreshing to see Elections Canada operate by voter-friendly rules. Voters could register on election day. Voters who had moved but not updated themselves on our registry could update their address on the voter rolls. And in particular…

Voter ID was not evil. In the US, requiring voters to show identification is branded as a right-wing tool for voter suppression. This works by limiting the acceptable identification to a short list which the suppressed voters are less likely to have. In contrast, Elections Canada accepted documents from a long and very flexible list as identification. And, for voters who had none of those documents, they could still vote if another voter vouched for them.

Very manual ballot counting. At the end of the voting day, we closed our doors to voters, and then spent an hour counting the votes in our ballot box by hand. As Deputy Returning Officer, I cut open my corrugated cardboard ballot box, and read each ballot myself. Another poll worker, who had other duties during the day, sat beside me and tallied the votes — and provided a check that I was not misreading. We then recounted and double-checked all ballots. We packaged ballots up into a series of envelopes, by hand, and sealed then signed each. We filled out a paper form with the Statement of the Vote for our poll division, by hand, making three carbonless copies.

Very manual results aggregation. How did the results get to Elections Canada, for aggregation into overall riding results? By the supervisor of my location calling the district office of Elections Canada, then coming to my desk, reading the numbers from my Statement of the Vote form to the district office. There was shouting to be heard over background noise. There was a frustrated repeating of misheard numbers. There was nary a web-hosted tally form in sight.

Security through simplicity, wide delegation, and many eyes. Of the 52,039 ballots cast in Vancouver Centre, 120 were cast in my polling division’s ballot box. I know exactly how many votes each candidate got. One the three copies of the Statement of the Vote form came home with me. And, I was present in the election room all day. All the ballot boxes in the room were sealed and on public display. I have high confidence that there was no gross tampering or ballot-box stuffing at our location. (In contrast to, say, this reporter’s experience at polling places in Tatarstan during the recent Russian election.) I am confident that no voting machine misrecorded votes, because there was no voting machine. I know that voters verified what their ballot said, because the ballot is simple, and each voter controlled the marks on their own ballot. Now there are limits to my confidence. I don’t have visibility into how Elections Canada aggregated my results into the total of 52,039. I wish that I could see a preliminary report of polling division results, to check against what I wrote in my form, before the results are declared final. But overall, I could verify more of the leaf nodes of the election tree in Canada than I could in Washington or California.

A very, very long day. The flip side of simplicity is lots of manual work. The downside (one of many) to holding an election during a pandemic is that many people who would ordinarily take the poll worker job declined. Elections Canada was scrambling for poll workers. My spouse and I signed up in part because we were younger, vaccinated, and thus less at risk; we felt we had a patriotic duty to step in. But they wanted us to work the whole day. We reported at 05:30h, and weren’t released until about 22:00h. We had only one meal break, and a couple of bio breaks. It was an interesting day. It was a fulfilling day. But boy, it was a looooong day.